Development, validity, and reliability of harm perception and attitudes questionnaire for smokers of roll-your-own and factory-made cigarettes: A pilot study in Southern Thailand

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: Understanding roll-your-own (RYO) and factory-made (FM) cigarette smokers’ perceptions of harm and their attitudes toward smoking is essential for identifying the barriers they face in effective smoking cessation counseling. However, there are few tools available for measuring these perceptions and attitudes among smokers of RYO and FM cigarettes.

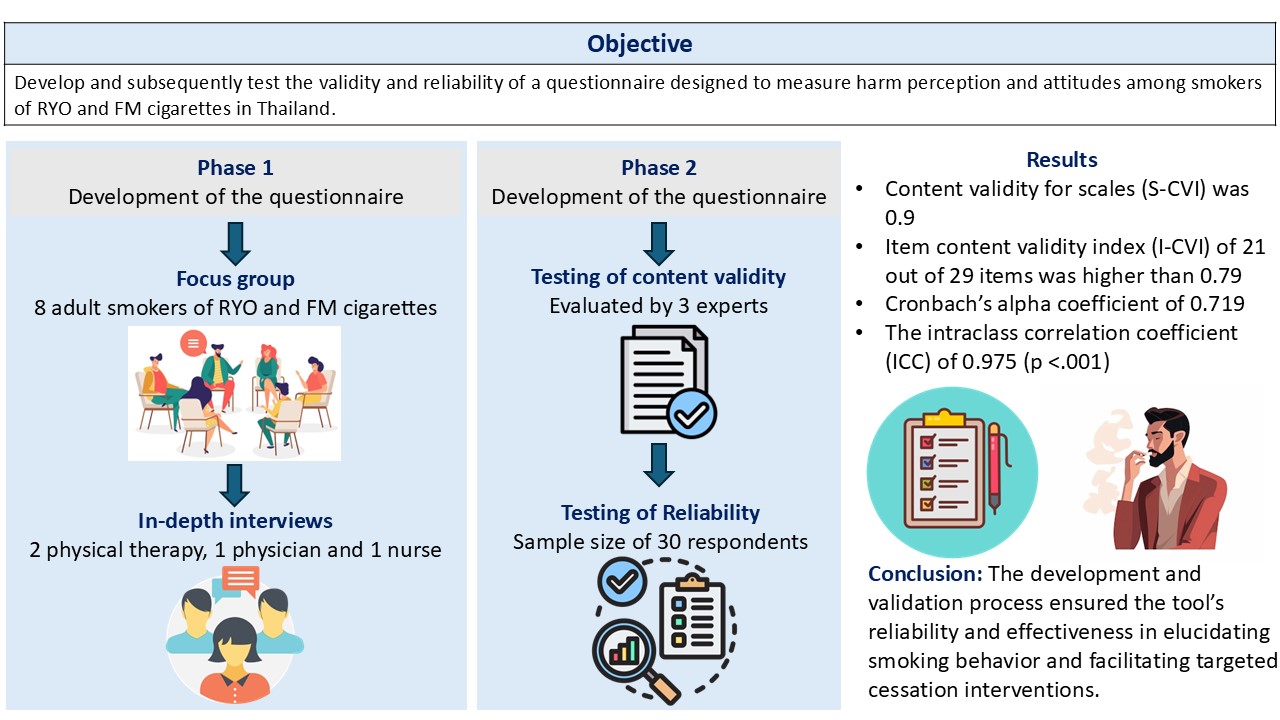

Objective: This study aimed to develop and subsequently test the validity and reliability of a questionnaire designed to measure harm perception and attitudes among smokers of RYO and FM cigarettes in Thailand.

Materials and methods: The questionnaire was developed based on data from focus groups with eight adult RYO and FM cigarette smokers and in-depth interviews with four medical professionals with experience in caring for smokers. The content validity of the questionnaire was measured by three experts. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was used to measure the internal consistency and reliability of the questionnaire. Data from 30 adult RYO and FM cigarette smokers were considered for the test-retest of reliability, measured using the intraclass correlation coefficient.

Results: The harm perception and attitudes questionnaire for RYO and FM cigarette smokers demonstrated good content validity. The item content validity index of 21 out of 29 items was higher than 0.79, and the scale content validity index was 0.9. Additionally, Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.719 and the intraclass correlation coefficient of 0.975 (p<0.001) indicated the good reliability of the tool.

Conclusion: This study presented a validated questionnaire to assess harm perception and attitudes among smokers of RYO and FM cigarettes. The development and validation process ensured the tool’s reliability and effectiveness in elucidating smoking behavior and facilitating targeted cessation interventions.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Personal views expressed by the contributors in their articles are not necessarily those of the Journal of Associated Medical Sciences, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

References

Young D, Yong HH, Borland R, Ross H, Sirirassanmee B, Kin F, et al. Prevalence and correlates of roll-yourown smoking in Thailand and Malaysia: findings of the ITC-South East Asia survey. Nicotine Tob Res. 2008; 10(5): 907-15. doi: 10.1080/14622200802027172.

Devlin E, Eadie D, Angus K. Rolling tobacco. Report prepared for the National Health Service. Scotland: The Centre for Tobacco Control Research, The University of Strathclyde; 2003; 1-16.

Engeland A, Haldorsen T, Andersen A, Tretli S. The impact of smoking habits on lung cancer risk: 28 years’ observation of 26,000 Norwegian men and women. Cancer Causes Control. 1996; 7(3): 366-76. doi: 10.1007/BF00052943.

Tuyns AJ, Esteve J. Pipe, commercial and handrolled cigarette smoking in oesophageal cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 1983; 12(1): 110-3. doi: 10.1093/ije/ 12.1.110

De Granda-Orive JI, Jimenez-Ruiz CA. Some thoughts on hand-rolled cigarettes. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011; 47(9): 425-46. doi: 10.1016/j.arbr.2011.02.013.

Joseph S, Krebs NM, Zhu J, Wert Y, Goel R, Reilly SM, et al. Differences in nicotine dependence, smoke exposure and consumer characteristics between smokers of machine-injected roll-your-own cigarettes and factory-made cigarettes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2018; 187: 109-15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep. 2018. 01.039.

Young D, Borland R, Hammond D, Cummings KM, Devlin E, Yong HH, et al. Prevalence and attributes of roll-your-own smokers in the ITC Four-Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006; 15(Suppl. 3): iii76-82. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013268.

Hung M, Spencer A, Goh C, Hon S, Cheever J, Licari W, et al. The association of adolescent e-cigarette harm perception to advertising exposure and marketing type. Arch Public Health. 2022; 80(1): 1-8. doi: 10.1186/ s13690-022-00867-6.

Jackson E, Tattan H, East K, Cox S, Shahab L, Brown J. Trends in harm perceptions of e-cigarettes vs cigarettes among adults who smoke in England, 2014-2023. JAMA Netw Open. 2024; 7(2): 1-13. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.0582.

Namwase S, Gyimah A, Carothers J, Combs B, Harris K. Changes in harm perception for e-cigarettes among youth in the United States, 2014–2019. Am J Health Promot. 2023; 37(4): 471-7. doi: 10.1177/ 08901171221133805.

Termsirikulchai L, Benjakul S, Kengganpanich M, Theskayan N, Nakju S. Thailand tobacco control country profile. Tobacco Control Research and Knowledge Management Center (TRC), Mahidol University, Bangkok, Charoendee Munkong Printing. http://www.who.int/fctc/reporting/annextwothai. pdf; 2008 [accessed 8 January 2024].

Healey B, Edwards R, Hoek J. Youth preferences for roll-your-own versus factory-made cigarettes: trends and associations in repeated national surveys (2006– 2013) and implications for policy. Nicotine Tob Res. 2016; 18(5): 959-65. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv135.

Benjakul S, Termsirikulchai L, Hsia J, Kengganpanich M, Puckcharern H, Touchchai C, et al. Current manufactured cigarette smoking and roll-your-own cigarette smoking in Thailand: findings from the 2009 Global Adult Tobacco Survey. BMC Public Health. 2013; 13(1): 277. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-277.

Bureau of Tobacco Control. Tobacco Products Control Act B.E. 2560 (2017). 1st Ed. Bureau of Tobacco Control, Department of Disease Control, Ministry of Public Health, Nonthaburi, Thailand: Bureau of Tobacco Control; 2017.

Aungkulanon S, Pitayarangsarit S, Bundhamcharoen K, Akaleephan C, Chongsuvivatwong V, Phoncharoen R, et al. Smoking prevalence and attributable deaths in Thailand: predicting outcomes of different tobacco control interventions. BMC Public Health. 2019;19(1):984. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7332-x.

Sandman PM Weinstein ND Hallman WK. Communications to reduce risk underestimation and overestimation. Risk Decis Policy. 1998;3(2):93–108. doi:10.1080/135 753098348220.

Sandman PM. Four kinds of risk communication. Synergist. 2003; 4: 26-7.

Lynn MR. Determination and quantification of content validity. Nurs Res. 1986; 35(6): 382-5. doi: 10.1097/00006199-198611000-00017.

Polit DF, Beck CT. The content validity index: are you sure you know what’s being reported? Critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health. 2006; 29(5): 489-97. doi: 10.1002/nur.20147.

Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: principles and methods. 7th Ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2004.

Bujang A, Omar D, Foo P, Hon K. Sample size determination for conducting a pilot study to assess reliability of a questionnaire. Restor Dent Endod. 2024; 49(1): 1-8. doi: 10.5395/rde.2024.49.e3.

Hinton PR, Brownlow C, Mcmurray I, Cozens B. SPSS explained. East Sussex, England: Routledge; 2004. doi: 10.4324/9780203642597.

Sharma B. A focus on reliability in developmental research through Cronbach’s alpha among medical, dental and paramedical professionals. Asian Pac J Health Sci. 2016; 3(4): 271-8. doi: 10.21276/apjhs. 2016.3.4.43.

Marx RG, Alia M, Lois H, Edward CJ, Russell FW. A comparison of two-time intervals for test-retest reliability of health status instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003; 56(8): 730-5. doi: 10.1016/S0895- 4356(03)00084-2.

Portney LG, Watkins MP. Foundations of clinical research: applications to practice. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson/Prentice Hall; 2009; 11-5.

Rosner B. Fundamentals of biostatistics. 4th Ed. Toronto: Duxbury Press; 1995.

Hammond D, Reid JL, Driezen P, et al. Perceived effectiveness of pictorial health warnings among smokers and non-smokers in Mexico: A crosssectional study. Tob Control. 2014; 23(1): e6.

Borland R, Yong HH, Wilson N, et al. How reactions to cigarette packet health warnings influence quitting: Findings from the ITC Four-Country survey. Addiction. 2012; 104(4): 669-75.

Thammawongsa P, Laohasiriwong W, Yotha N, Nonthamat A, Prasit N. Influence of socioeconomics and social marketing on smoking in Thailand: A National Survey in 2017. Tob Prev Cessat. 2023; 9:28. doi: 10.18332/tpc/169501.

Sornpaisarn B, Parvez N, Chatakan W, Thitiprasert W, Precha P, Kongsakol R, et al. Methods and factors influencing successful smoking cessation in Thailand: A case-control study among smokers at the community level. Tob Induc Dis. 2022; 20: 67. doi: 10.18332/ tid/150345

Mukherjea A, Morgan PA, Snowden LR, Ling PM, Ivey SL. Social and cultural influences on tobaccorelated health disparities among South Asians in the USA. Tob Control. 2012; 21(4): 422-8. doi: 10.1136/ tc.2010.042309.

Sa R, Paek SC. Changes in the socioeconomic pattern of smoking among male adults in Thailand from 2001 to 2021. Sage Open. 2024; 14(2): 21582440241252494. doi: 10.1177/21582440241252494.

Jitnarin N, Kosulwat V, Rojroongwasinkul N, Boonpraderm A, Haddock CK, Poston WS. Socioeconomic status and smoking among Thai adults: results of the National Thai Food Consumption Survey. Asia Pac J Public Health. 2011; 23(5): 672-81. doi: 10.1177/ 1010539509352200.

Chapman S, Freeman B. Regulating the tobacco retail environment: Beyond reducing sales to minors. Tob Control. 2008; 17(2): 137-42.

Chotbenjamaporn P, Phanuphak N, Thongcharoen P. Impact of graphic health warnings on smoking prevalence in Thailand. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2022; 23(6): 1763-70.

Chellappa LR, Balasubramaniam A, Indiran MA, Rathinavelu PK. A qualitative study on attitude towards smoking, quitting and tobacco control policies among current smokers of different socioeconomic status. J Family Med Prim Care. 2021; 10(3): 1282-7. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_1628_20.

Krist AH, Davidson KW, Mangione CM, et al. US Preventive Services Task Force. Interventions for tobacco smoking cessation in adults, including pregnant persons: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2021; 325(3): 265-79. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.25019.