Cause-specific mortality in reproductive-age breast cancer patients: A competing risk approach

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: Breast cancer (BC) is a leading cause of mortality among women, particularly those in the reproductive age (15-49 years).

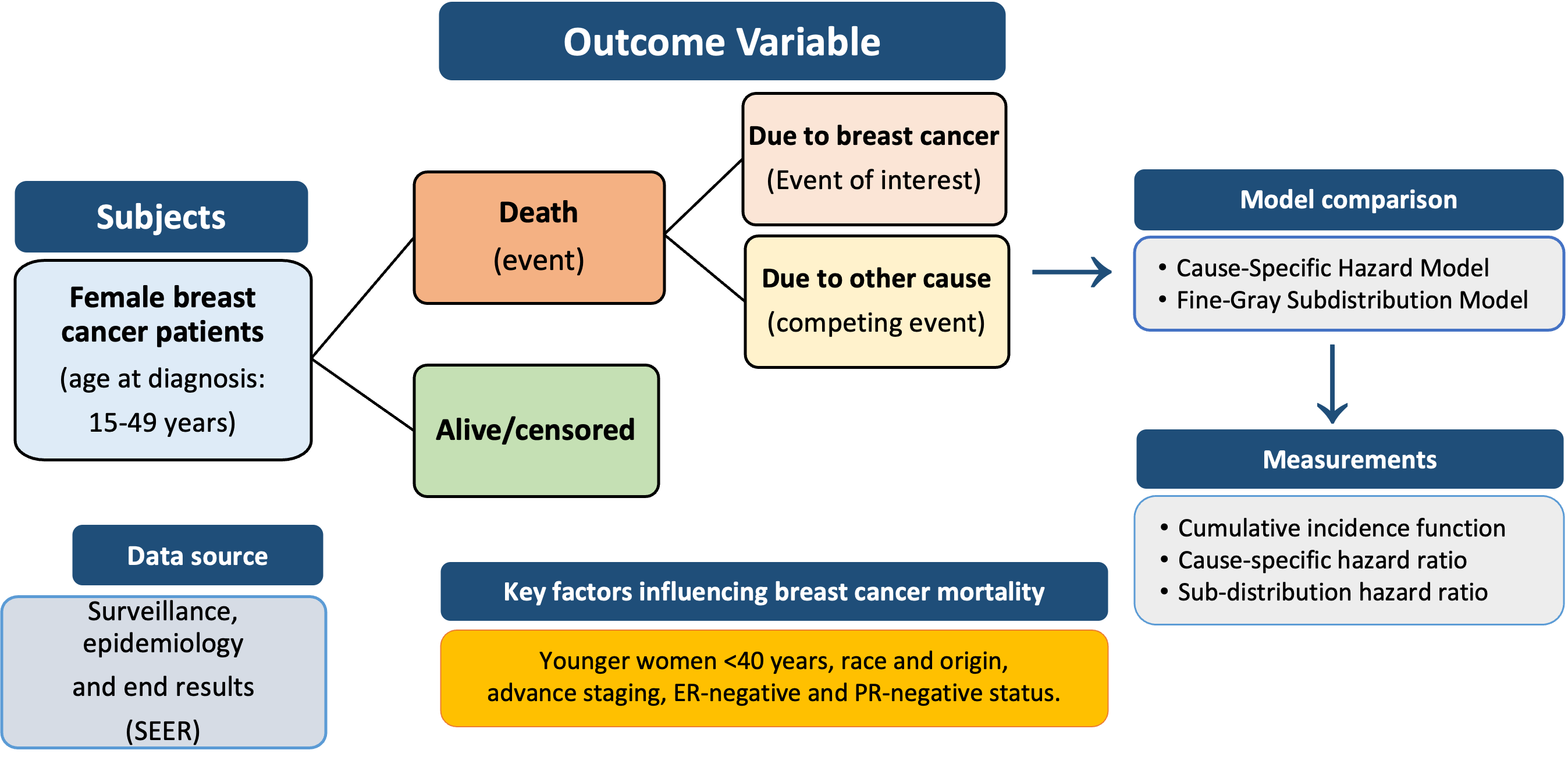

Objective: This study aims to examine the survival outcomes of female BC patients in reproductive age groups using a competing risk approach, with a focus on identifying significant determinants of BC-specific mortality and mortality due to other causes.

Materials and methods: This study utilized data from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database. The analysis included women diagnosed with breast cancer within reproductive age groups. The Cumulative Incidence Function (CIF), cause-specific hazard, and Fine-Gray subdistribution hazard models were employed to estimate the impact of potential determinants on BC-specific and other-cause mortality.

Results: A total of 67063 patients were included in the study. The cumulative incidence of breast cancer-specific mortality and other cause mortality at 5 years was 4.8% and 0.95%, respectively. Age at diagnosis, race, tumor stage, and hormone receptor status were significant predictors of breast cancer-specific mortality. The Fine-Gray model revealed that younger age (15-39 years), advanced tumor stage, and negative hormone receptor status were associated with higher hazards for breast cancer mortality (p<0.05).

Conclusion: The study highlights the importance of using a competing risk model to evaluate the cumulative incidence of prognostic factors in breast cancer patients of reproductive age, especially when competing clinical risks are present. These findings can guide personalized treatment strategies based on individual risk profiles.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Personal views expressed by the contributors in their articles are not necessarily those of the Journal of Associated Medical Sciences, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

References

Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71(3): 209-49. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660.

Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2019; 11: 151-64. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S176070.

Khalis M, Charbotel B, Chajès V, Rinaldi S, Moskal A, Biessy C, et al. Menstrual and reproductive factors and risk of breast cancer: A case-control study in the Fez region, Morocco. PLoS One. 2018; 13(1). doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0191333.

Mao X, Omeogu C, Karanth S, Wilson S, Vadlamudi N, Liao Y, et al. Association of reproductive risk factors and breast cancer molecular subtypes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2023; 23:644. doi: 10.1186/s12885-023-11049-0.

Kaplan EL, Meier P. Nonparametric estimation from incomplete samples. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958; 53(282):457-81. Available from: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2281868.

Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. J R Stat Soc Ser B. 1972; 34(2): 187-220.

Huque MF, Sankoh AJ. A reviewer’s perspective on multiple endpoint issues in clinical trials. J Biopharm Stat. 1997; 7(4): 545-64. doi: 10.1080/10543409708835206.

Dignam JJ, Kocherginsky MN. Choice and interpretation of statistical tests used when competing risks are present. J Clin Oncol. 2008; 26(24): 4027-34. doi:10.1200/JCO.2007.12.9866.

Prentice RL, Kalbfleisch JD, Peterson AV, Flournoy N, Farewell VT, Breslow NE. The Analysis of Failure Times in the Presence of Competing Risks. Biometrics. 1978; 34(4): 541-54. Available from: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2530374.

Fine JP, Gray RJ. A Proportional Hazards Model for the Subdistribution of a Competing Risk. J Am

Stat Assoc. 1999; 94(446): 496-509. doi: 10.1080/01621459.1999.10474144.

National Cancer Institute. SEER Cancer Statistics.2020. Available from: https://seer.cancer.gov/

Satagopan JM, Stroup A, Kinney AY, Dharamdasani T, Ganesan S, Bandera EV. Breast cancer among Asian Indian and Pakistani Americans: A surveillance, epidemiology and end results-based study. Int J Cancer. 2021; 148(7): 1598-607. doi: 10.1002/ijc.33331.

Solanki PA, Ko NY, Qato DM, Calip GS. Risk of cancerspecific, cardiovascular, and all-cause mortality among Asian and Pacific Islander breast cancer survivors in the United States, 1991–2011. Springerplus. 2016; 5(1): 1-12. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1726-3.

Pham MH, Kafle RC. Competing Risks Analysis of African American Breast Cancer Patients. Adv

Breast Cancer Res. 2017; 6(1): 28-41. doi: 10.4236/abcr.2017.61003.

Keegan THM, Tao L, DeRouen MC, Wu XC, Prasad P, Lynch CF, et al. Unmet adolescent and young adult cancer survivors information and service needs: A population-based cancer registry study. J Cancer Surviv. 2012; 6(3): 239-50. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0219-9.

Lord SSJ, Marinovich ML, Girgis A, Emery JD, Gill TK, Sullivan R, et al. Long term risk of distant metastasis in women with non-metastatic breast cancer and survival after metastasis detection: a population-based linked health records study. Med J Aust. 2022; 217(8): 402-9. doi: 10.5694/mja2.51687.

Kim HJ, Han W, Yi OV, Lee MH, Lee KH, Hwang KT, et al. The impact of young age at diagnosis (age <40 years) on prognosis varies by breast cancer subtype: A U.S. SEER database analysis. Breast. 2022; 61: 77-83. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2021.12.006.

Du XL, Fox EE, Lai D. Competing causes of death for women with breast cancer and change over time from 1975 to 2003. Am J Clin Oncol. 2008; 31(2):105-16. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e318142c865.