Cognitive intervention using Montessori and DementiAbility for people with mild cognitive impairment

Main Article Content

Abstract

Background: Age-related illnesses are more prevalent with advancing age, with seniors facing more chronic diseases and disabilities. Chronic diseases that mostly older adults deal with are caused by high blood pressure, diabetes, and high cholesterol-also called noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). NCDs can cause severe chronic diseases such as heart disease, kidney failure, and cerebrovascular disease, and these can result in a high risk of Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). Together, brain cells shrink around 2,000 million cells when getting older, causing difficulty recalling names or words, decreased attention span, or a decreased ability to handle many tasks simultaneously. Therefore, protecting senior citizens with MCI needs to be seriously consideration.

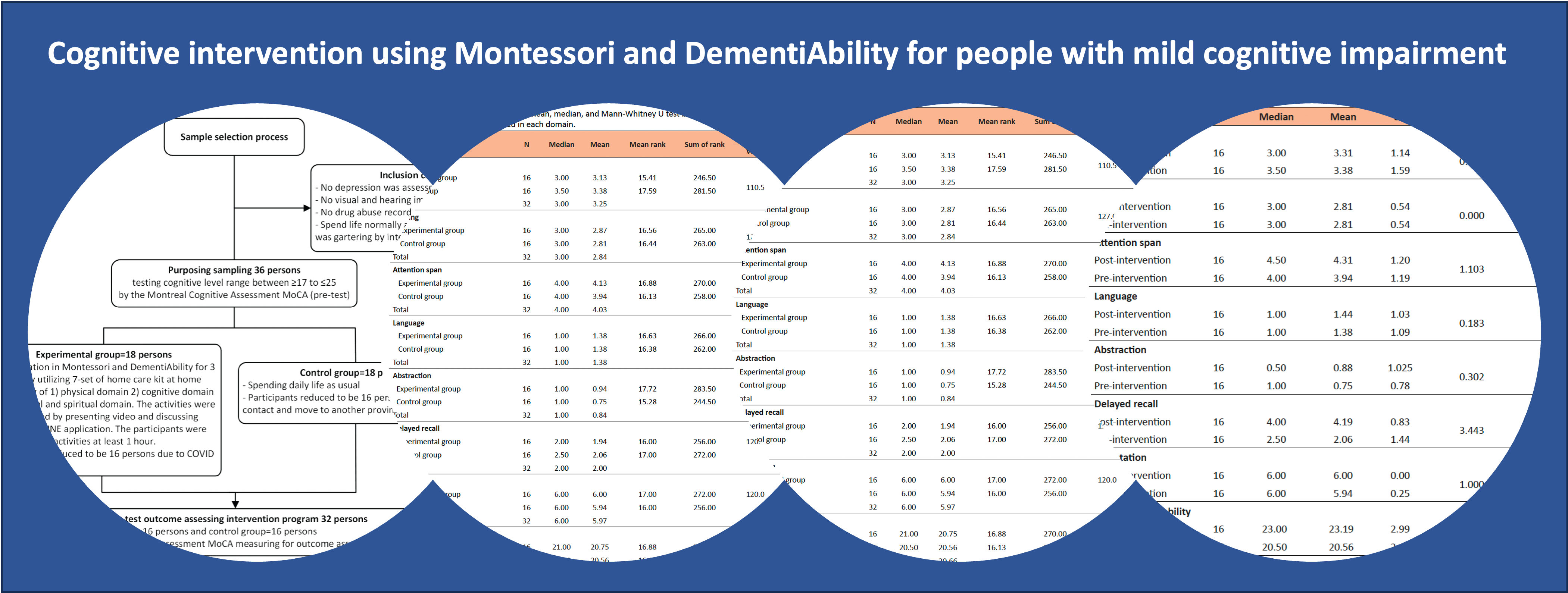

Objectives: This quasi-experimental research aimed to study the effects of a program to reduce brain deterioration in older people with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI).

Materials and methods: The samples consisted of senior males and females requiring service at Songkhla Rajanagarindra Psychiatric Hospital, Songkhla, Thailand. A sample group was selected using an equivalent group design. The researcher utilized inclusion and exclusion criteria to gather 32 older adults and employed a simple random selection into experimental and control groups. For three months, the experimental group engaged in a seven-care-kit program based on Montessori’s philosophy and DementiAbility methods to help protect against brain deterioration. Mann-Whitney U test and Wilcoxon Value were used to analyze the result of the program’s effectiveness, which assessed cognitive ability by MoCA.

Results: The attention span domain showed a significant statistical difference at (p=0.03) after post-tests comparing the experimental and control groups. A comparison of the pre-test and post-test of the experimental group found four domains-total cognitive domain, attention span domain, delayed recall domain, and visuospatial perception domain were significant with a statistical difference of (p=0.001, p=0.002, p=0.003, and p=0.004 respectively). Moreover, two domains- the delayed recall domain and the total cognitive domain in the control group showed a significant statistically increasing difference at (p=0.001 and p=0.005, respectively).

Conclusion: The senior citizens’ active daily activities may help protect against dementia in older adults with MCI. The Home-Based Protection of Brain Deterioration Program demonstrated a satisfactory program that enhanced the attention span, visuospatial domain, and delayed recall of older people with mild cognitive impairment. Hence, the program as a dementia prevention program for older adults with MCI.

Article Details

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Personal views expressed by the contributors in their articles are not necessarily those of the Journal of Associated Medical Sciences, Faculty of Associated Medical Sciences, Chiang Mai University.

References

Department of Older People. National Senior Citizen of the Year 2020: Amarin Printing and Publishing Public Company Limited, Bangkok, Thailand; 2020.

Franceschi C, Garagnani P, Morsiani C, Conte M, Santoro A, Grignolio A, et al. The continuum of aging and age-related diseases: Common mechanisms but different rates. Front Med (Lausanne). 2018; 12 (5). doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00061. PMID: 29662881; PMCID: PMC5890129.

Nukred B. Ageing Nursing. Bangkok: Yuttarin Printing Co; 2007.

Chasirikarn S, Janvetsaman P. Exercise brain manual. 2nd Ed. Bangkok: We print; 2008.

Farias ST, Cahn-Weiner D, Harvey D, Reed B, Mungas D, Kramer JH, Chui H. Longitudinal changes in memory and executive functioning are associated with longitudinal change in instrumental activities of daily living in older adults. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009; 23: 446-61.

Sommerlad A, Sabia S, Singh-Manoux A, Lewis G, Livingston G. Association of social contact with dementia and cognition: 28-year follow-up of the Whitehall II cohort study. PLoS Med. 2019; 16(8): e1002862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002862.

Pellecchia A, Kritikos M, Guralnik J, Ahuvia I, SantiagoMichels S, Carr M, Kotov R, Bromet EJ, Clouston SAP, Luft BJ. Physical functional impairment and the risk of incident Mild Cognitive Impairment in an observational study of World Trade Center responders. Neurol Clin Pract. 2022; 12(6): 162-171. doi: 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000200089.

Stieger M, Lachman ME. Increases in cognitive activity reduce aging-related declines in executive functioning. Front Psychiatry. 2021; 12: 708974. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2021.708974.

Samael L, Thaniwattananon P, Kong-in W. The Effect of Muslim-Specific Montessori-Based Brain-Training Program on Promoting Cognition in Muslim Elderly at Risk of Dementia. Princes of Naradthiwas University Journal. 2016; 8: 16-21.

Jeeraya S, Hengudomsub P, Vatanasin D, Pratoomsri, W. Effects of cognitive stimulation program on perceived memory self-efficacy among older adults with mild cognitive impairment. JFONUBUU 2018; 26(2): 30-9.

Apichonkit S, Narenpitak A, Mudkong U, Awayra P,

Pholprasert P, Pichaipusit A. Effectiveness of a cognitive function’s improvement program in elderly MCI patients of primary care unit network of Udonthani Hospital. Udonthani 2019; 27(2): 138-49. (in Thai).

Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): Recent evidence and development of a shorter version. Clin Gerontol. 1986; 5(1-2): 165-73. doi: 10.1300/J018v05n01_09.

Wongpakaran N, Wongpakaran T, Van Reekum R. The Use of GDS-15 in Detecting MDD: A Comparison Between Residents in a Thai Long-Term Care Home and Geriatric Outpatients. J Clin Med Res. 2013; 5(2): 101-11. doi: 10.4021/jocmr1239w

Nasreddine ZS, Phillips NA, Bedirian V, Charbonnean S, Whitehead V, Collin I, Cummings JL, Chertkow H. The Montreal Cognitive Assessment, MoCA: A brief screening tool for Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2005; 53(4): 695-9.

Hemrungrojn S. MoCA Thai version 2007. In: MoCA Montreal - Cognitive Assessment. 2011.

Tulving E. Memory and consciousness. Can Psychol. 1985; 26(1): 1-12. doi: 10.1037/h0080017.

Tulving E. Concepts of memory. In: Tulving E, Craik FIM, editors. The Oxford Handbook of Memory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. p. 33-43.

Jonides J, Lewis RL, Nee DE, Lustig CA, Berman MG, Moore KS. The mind and brain of short-term memory. Annu Rev Psychol. 2008; 59: 193-224. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.59.103006.093615.

Postle BR. Working memory as an emergent property of the mind and brain. Neuroscience. 2006; 139(1): 23-38. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.005.

Oberauer K. Working Memory and Attention: A Conceptual Analysis and Review. J Cogn. 2019; 8(2): 3-23. doi: 10.5334/joc.58.

Oberauer K, Souza AS, Druey M, Gade M. Analogous mechanisms of selection and updating in declarative and procedural working memory: experiments and a computational model. Cogn Psychol. 2013; 66: 157- 211. doi: 10.1016/j.cogpsych.2012.11.001

Meiran N, Liefooghe B, De Houwer J. Powerful instructions: Automaticity without practice. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2017; 26(6): 509-14. doi: 10.1177/0963721417711638.

Nilakantan AS, Bridge DJ, VanHaerents S, Voss JL. Distinguishing the precision of spatial recollection from its success: Evidence from healthy aging and unilateral mesial temporal lobe resection. Neuropsychologia. 2018; 119: 101-6. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2018.07.035.

Montero-Odasso M, Muir SW, Speechley M. Dual-task complexity affects gait in people with mild cognitive impairment: the interplay between gait variability, dual tasking, and risk of falls. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93: 293-9.

Bong M. Age-Related differences in achievement goal differentiation. J Educ Psychol. 2009; 101(4): 879-96.

Diamond M. C. An optimistic view of the aging brain. GENERATIONS. 1993; 17 (1): 31-3.

Demarin V, Morović S. Neuroplasticity. Periodicum Biologorum. 2014; 116, (2): 209-11.

Fuchs E, Flügge G. Adult neuroplasticity: More than 40 years of research. Neural plast. 2014; 541870. doi.org/10.1155/2014/541870.

Vance D, Camp C, Kabacoff M, Greenwalt L. Montessori methods: Innovative interventions for adults with Alzheimer’s disease. Montessori Life. 1996; 8: 10-2.

Presmeg N. Research on visualization in learning and teaching mathematics. In: Gutiérrez A, Boero P, editors. Handbook of research on the psychology of mathematics education: Past, Present and Future. Rotterdam: Sense; 2006. p. 205-236.

Wells DL, Dawson P. Description of retained abilities in older persons with dementia. Res Nurs Health. 2000; 23(2): 158-66.

Owen R, Berry K, Brown LJ. Enhancing older adults’ well-being and quality of life through purposeful activity: A systematic review of intervention studies. Gerontologist. 2022; 62: e317-e32.

Sutin AR, Aschwanden D, Luchetti M, Stephan Y, Terracciano A. Sense of purpose in life is associated with lower risk of incident dementia: A Meta-Analysis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021; 83(1): 249-58. doi: 10.3233/JAD-210364.